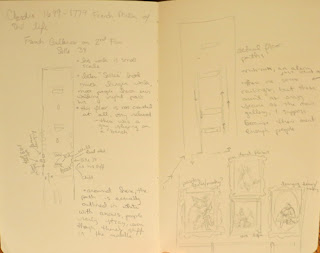

For my time at the Louvre, I focused on Chardin’s Le Singe antiquaire-left (1726), and Chimiste dans son Laboratoire-right (1726). They were in the French Gallery on the second floor away from most of the floor traffic. The atmosphere was far more relaxed, to the point that there was a man napping by the window. Very few people traveled there and I saw no tour groups. This gallery was laid out with specific paths on the floor, arrows included and it was split into two small sections and two large. Few people strayed from the paths to looks at the art in the center of the smaller sub-galleries. Chardin’s work was spread throughout the whole gallery.

To the right of Le Singe, through the doorway in the next gallery, was Chardin’s Chimiste dans son Laboratoar, another academic, but he was human. Few people stopped to glance at these pieces, fewer to actually look. I got the impression that some people only looked because they saw me drawing it and were curious what the painting was. For how interesting some of Chardin’s work is, it got little attention. This quick walk though could be contributed to the drawn out pathways and arrows on the floor, the location of the galleries, the location of the paintings on the wall, or that people were so exhausted from the rest of the museum, they didn’t have the energy to look at much more.

|

| gallery maps |

In both of Chardin’s

paintings, he depicts academics leisurely (the relaxed atmosphere of the gallery mimics the positions of the figures) enjoying their books facing opposite

directions. The compositions are

similar. They are centered vertically off centered horizontally with the

subject facing center. In Chimiste, the tone is more straightforward and

literal, while the artist’s decision to use a monkey in Le Singe takes a bit

more interpretation. Using a

monkey to depict a scholar and a painter (opposite of the dead rabbit and still

life) seems to be mocking the two professions. The monkey is similar to some earlier work, like the Flemish

artist Teniers the Youner. Tenier

painted very similar scenes of anthropomorphic animals. Chardin’s choice

for a subject might reflect this thought.

Perhaps Chardin’s decision to make the bottles in Chimiste so secondary

is a similar idea, as if he does not want us to take this chemist

seriously. The chemist looks

relaxed, not hard at work. The monkey and the chemist are not parodies and Chardin likely does not think highly of scholars and academics, himself included, as there was a monkey painting in the same gallery.

The experience of Versilles

was overwhelming: in scale, luxury, and tourism. The gardens were so ridiculous and beautiful, it’s hard to

believe they were built for so few people to enjoy. It wasn’t hard to believe how upset the Palace of Versailles

made the rest of France feel and the revolution it helped start. With those thoughts in mind, it was

difficult to actually enjoy them.

The money put into building and to maintain Versailles over all these

years amazes me. If the

extravagance of the palace upset the French before, I am curious to know how they

feel about it now. It is a

treasure that would be an absolute shame to lose, a main tourist spot, and must

provide a lot of jobs. The cost of

maintenance (cleaning, gardening, etc.) and conservation must cost a

fortune. Even the new work (the

tree installations and marble or plaster sculptures) must be expensive. Versailles is still a symbol of

unnecessary decadence, not much different than before. While I would never wish for it to fade

and become overgrown, thinking of the money continuously being put into the

Palace and garden seems so contrary to what the French wanted in the

Revolution.

No comments:

Post a Comment